-

Alaskan Way Seawall

1951 Alaskan Way

The story of the seawall and the Pier 62 park

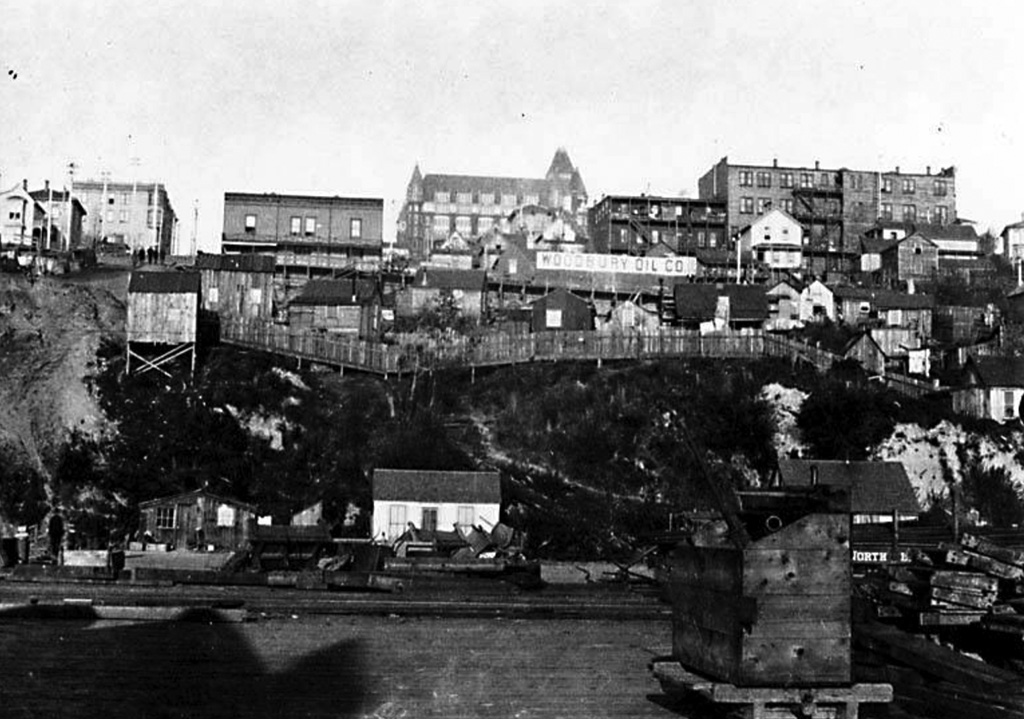

Though the early waterfront-on-pilings served its purpose, maintenance of the pilings and the planking on top of them proved difficult. Parts of the trestles sometimes collapsed under the weight of traffic, especially as trucks with more powerful engines could carry heavier loads. The city finally built a permanent seawall along the central waterfront between Madison and Bay streets in 1936. Along with the wall built south of Madison in 1916, this completed the transformation of the central waterfront from beach to dry land, protected from the tides and raised to the level of Western Avenue with fill brought in from the mouth of the Cedar River by scow and dumped behind the wall.

This northern section took longer to build primarily because of the costs involved in building a wall that could hold back the fill, which was pulled seaward by the slope of the beach, and reach high enough to stay above the highest tides, when the water could reach 36 feet in depth. Engineers solved the problem by designing a two-part wall with concrete slabs on top of corrugated steel sheet pilings that were driven into the seafloor. A wooden support structure on the inland side, held in place by the weight of hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of fill on top and around it, counteracted the pull of gravity and held the wall upright. The filled area behind the seawall created space for a permanent street for vehicles and trains and one of Seattle’s most persistent problems: traffic. The newly opened Alaskan Way quickly became a downtown bypass route, to the dismay of railroads and waterfront business owners who had to negotiate the crowded thoroughfare to access the piers.

By the time the Nisqually Earthquake hit in 2001 and jumpstarted efforts to replace the Alaskan Way Viaduct, the seawall was desperately in need of replacement, too. Teredos and gribbles, both small, invertebrate marine borers, had chewed their way through much of the wooden element of the seawall, leaving it vulnerable to collapse.

If you walk to the south side of Pier 62 and look back toward Alaskan Way and under the sidewalk, you can see the new seawall. It is also a sheet pile and face panel wall anchored back to an inland structure, but instead of wood, the structure is constructed with concrete and jet grout columns, which are created by the injection of grout into the soil. The grout hardens and creates a solid structure to anchor the seawall. The concrete face of the seawall was precast in molds with a cobbled texture, providing space for vegetation to grow. The habitat bench that juts out from the wall also has a cobbled texture and vegetation. The vegetation attracts smaller organisms and encourages salmon, especially juveniles, to migrate along the wall.

Pier 62 Park was the first part of the new waterfront redevelopment project to open. Originally the two piers here, Pier 62 and 63, were built for handling cargo handling. Pier 62, known as the Gaffney Dock, was built in 1901 and was associated with the complex of fishing piers that extended south, to where the Seattle Aquarium is today. It was named for its owner, Mary A. Gaffney, who also owned a significant amount of property around the city. Pier 63, known as the Virginia Street Dock, first served as a terminal for steamship lines that carried passengers and freight between Seattle and ports in Alaska and California. It later was used as a warehouse for newsprint from Canada that was sold to area newspapers. Puget Sound Freight Lines carried cargo through the dock until the 1970s. After a period of disuse, the piers became home to the Summer Nights at the Pier concert series until the pilings deteriorated and the pier could no longer support the crowds. Pier 62 has been rebuilt as a city park and a new floating dock has been added to its south side. Pier 63 was demolished in 2022.