-

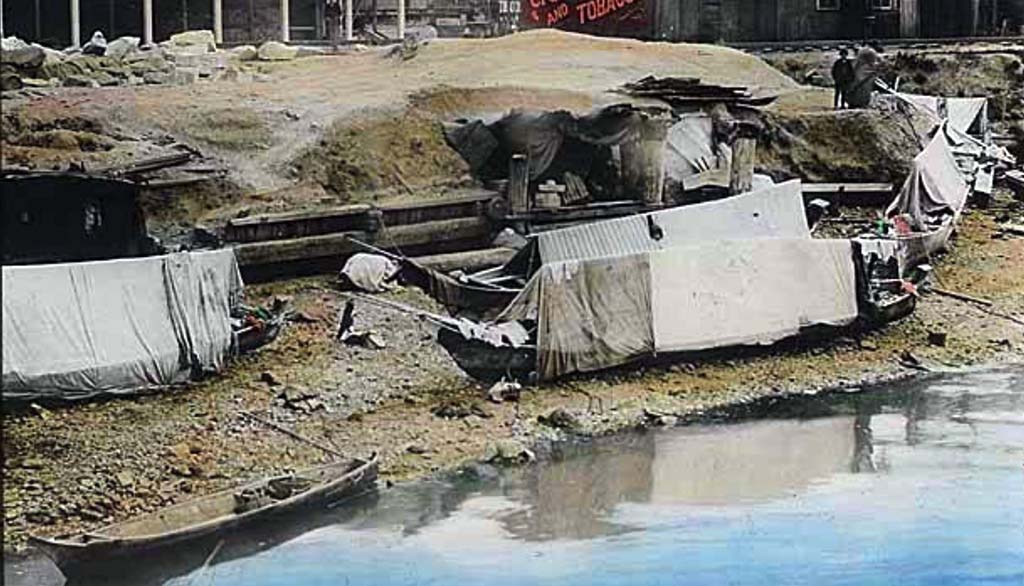

Ballast Island/OIC dock

Alaskan Way and Main Street

Alaskan Way and Washington/Main

The shoreline at this point was originally more than 200 feet inland. In about 1880, as more ships began coming to Elliott Bay to load lumber and coal for export, an island-like mound began to appear in the area where Alaskan Way and Pier 48 meet that was composed of rocks and other materials taken on as ballast from locations around the world, including 40,000 tons from San Francisco’s Telegraph Hill. The ballast was needed to improve stability in the nearly empty ships that came to Seattle when exports of raw materials far exceeded the imports for local markets. The Oregon Improvement Company’s City Dock and Ocean Dock, at Main and Washington streets respectively, could accommodate four ships simultaneously, and as they dumped their ballast to make room for cargo, Ballast Island grew rapidly. At its peak, it reached 400 feet into Elliott Bay.

This “made land” became an important place for Native people who came to Seattle to work, conduct business, and socialize. Members of local tribes and others from distant tribes, some from as far north as Alaska, stopped at Ballast Island because it was the only place adjacent to the business district where non-Native residents did not actively resist their presence, although, even there, their camps were sporadically forcefully cleared by the dock owners. Many Native people stopped at Ballast Island on their way to and from the Green and Puyallup river valleys to the south, where they picked fruit and hops. As Railroad Avenue, the “street” on pilings running just east of Ballast Island, and the piers grew in the 1890s, they covered over the island, first with the elevated structures and then, once the seawall along this portion of the waterfront was built in 1916, with fill.

The Oregon Improvement Company Ocean Dock was also involved in one of Seattle’s most notorious racist incidents. Beginning in the 1860s, hundreds of Chinese immigrants had come to the Washington Territory to build railroads, mine, and can salmon. Although they worked hard at difficult and sometimes dangerous jobs, they were generally paid less than white laborers due to discriminatory employment practices. This created another layer of cultural conflict, as white laborers came to view the Chinese workers as unfair competitors.

Due to this antagonism and rampant anti-Asian racism all along the West Coast, in 1882 Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which severely restricted Chinese immigration to the United States. By 1885 anti-Chinese agitation had reached a peak, and Chinese workers were being run out of town in communities throughout the region. On February 6, 1886, an anti-Chinese meeting was held in Pioneer Square, and the next day, a throng of white workers, from Seattle and surrounding areas, encouraged by labor leaders, rounded up approximately 350 Chinese from Seattle’s Chinatown and herded them to the waterfront for passage out of town on a waiting steamer, the Queen of the Pacific, at the Ocean Dock.

Territorial Governor Watson Squire happened to be in Seattle and ordered the mob to desist and disperse but violence erupted the next day when the mob attacked Home Guards, a self-appointed unit that protected the commercial district and the Chinese residents from the rioters. Martial law was declared, and President Grover Cleveland ordered U.S. troops to Seattle. Even with this intervention most of the city’s Chinese population was forced out of the city. Passions gradually cooled in Seattle but it took 20 years for Seattle’s Chinese population to return to its pre-expulsion levels.

In an echo of the past, in 1942, the Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island, who were forced into incarceration camps as a result of Executive Order 9066 requiring all residents of Japanese descent to leave the West Coast, crossed over this same upland area as they walked between the ferry landing and the train waiting to carry them inland to the camps.