-

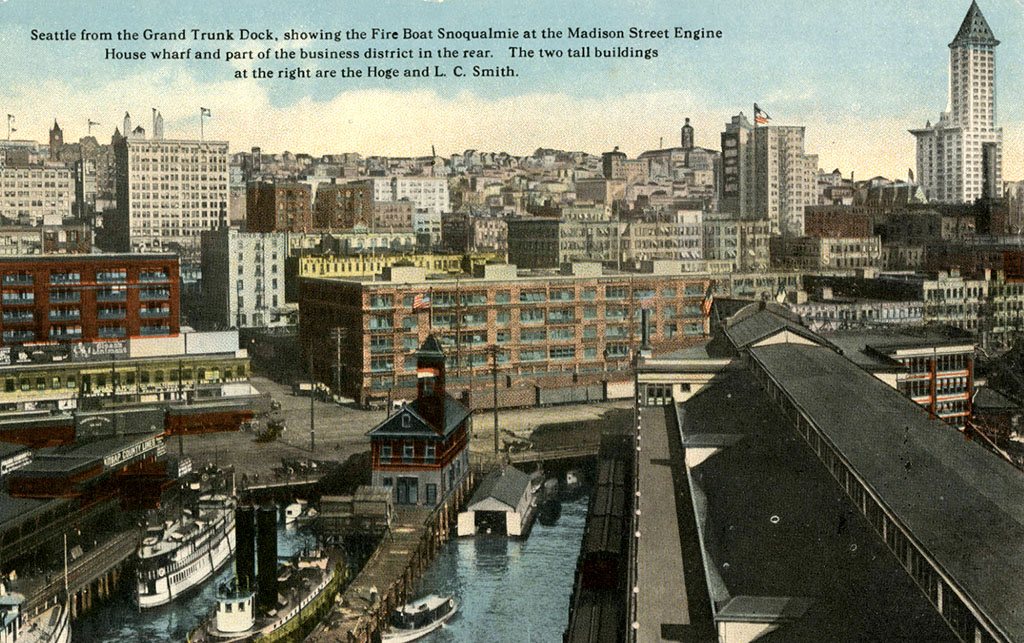

Maritime Building – Commission District

906 Alaskan Way

Madison and Western, looking at Maritime Building

Western Avenue was once Seattle’s warehouse district. Much of the produce and other goods coming into the piers along Railroad Avenue (now Alaskan Way) from around Puget Sound passed through buildings like the Maritime Building on the northwest corner and others between Yesler Way and Union Street like the National Building at 1008 Western Avenue, the Carstens Building at 815 Western Avenue, and the Polson Building at 61 Columbia Street.

In the 1900s, the area was known as the Commission District, where wholesalers who bought produce, dairy products, and eggs from Puget Sound farmers sold to retail outlets. Their control (and manipulation) of prices to the detriment of farmers and consumers led to the establishment of the Pike Place Market, where farmers could sell directly to consumers, in 1907.

Some of the buildings had meat packing operations. In 1908, Commissioner of Health J. F. Crighton found, “tons and tons of refuse from the chicken section” amongst the pilings supporting a meat company (the area between the foundation and the beach lay exposed at all but the highest tides) — apparently a hole in the floor had served as a “garbage chute” for the offal from the meat processing. One can only imagine the stench that emanated from beneath the buildings. The multitude of rats attracted by these conditions proved a nuisance, not least because they caused a small outbreak of bubonic plague in 1908.

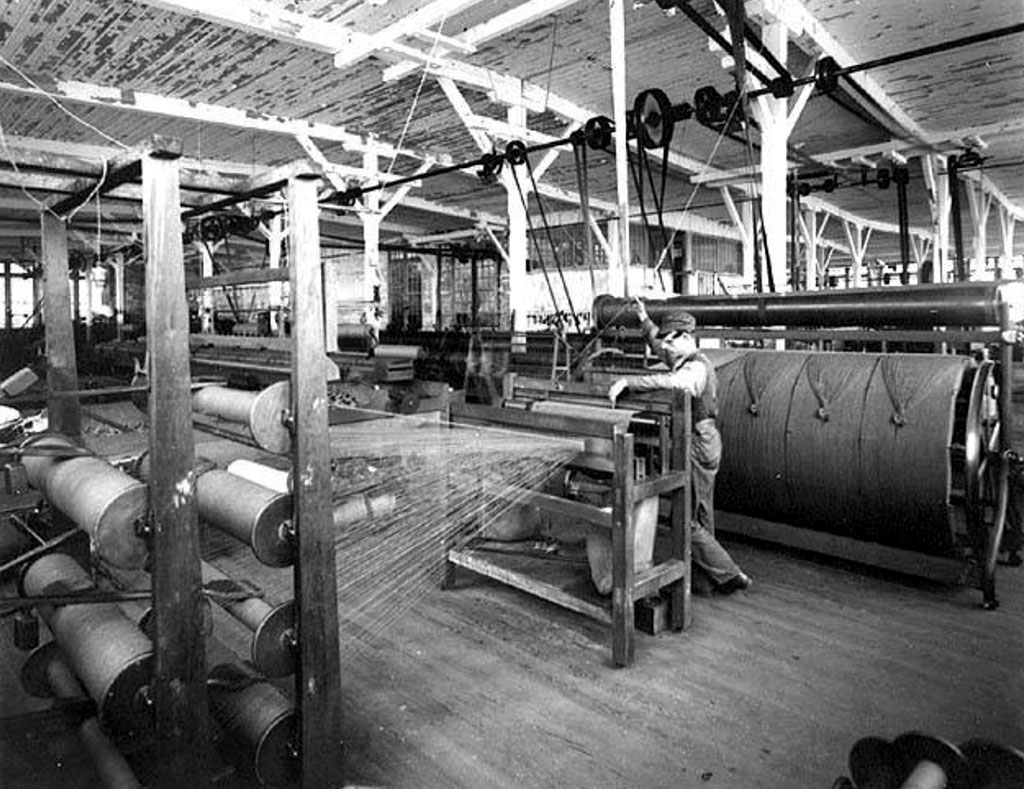

In order to handle the weight of machinery and the goods stored in the building, architect Edwin W. Houghton, who also designed local theaters such as the Moore Theater, had the floors of the Maritime Building constructed to carry 250 pounds per square foot (the average load for an office building floor is 50 pounds per square foot) by using enormous timbers in the post and beam construction. In addition to supporting the heavier load, this design required fewer vertical supports, leaving the floors more open for a wider variety of uses.

The north, east, and south sides of the building accommodated storefronts, but the west side was designed for loading and a spur railroad line ran right along building. You can still see this configuration of railroad tracks and loading docks along the west sides of several buildings along Alaskan Way.

In the 1930s, the Maritime Building still had five food-related firms, selling groceries, produce, tea, and coffee, but there were some new light industrial uses including brokers for fire apparatus and supplies and John Deere plows, printers, paper and stationery companies, and I. F. Laucks, which invented Lauxein, a soybean glue used to make plywood. Lauxein and other soy-based glues were replaced with synthetic glues after World War II, but they have made a resurgence in part because of the health effects of formaldehyde and other chemicals in the synthetic formulas. The building also housed a mining company, the Seattle Woolen Company, and Hughes & Adams coffee roasters (makers of the “Smilax – A smile in every cup” blend), among others.

In the late 1960s, the building would, like the rest of the Central Waterfront, begin to see more professional offices, rather than light industrial uses or sales offices. A branch of the National Maritime Bank opened in 1967 and the Young Men’s Republican Club also opened that year. By the 1980s light industry had largely been moved out of the Commission District buildings. A shift to professional offices and residential uses began that would later be codified in the area’s zoning. Today, the historic buildings, a number of them city landmarks, house apartments, condominiums, offices, and retail stores.