-

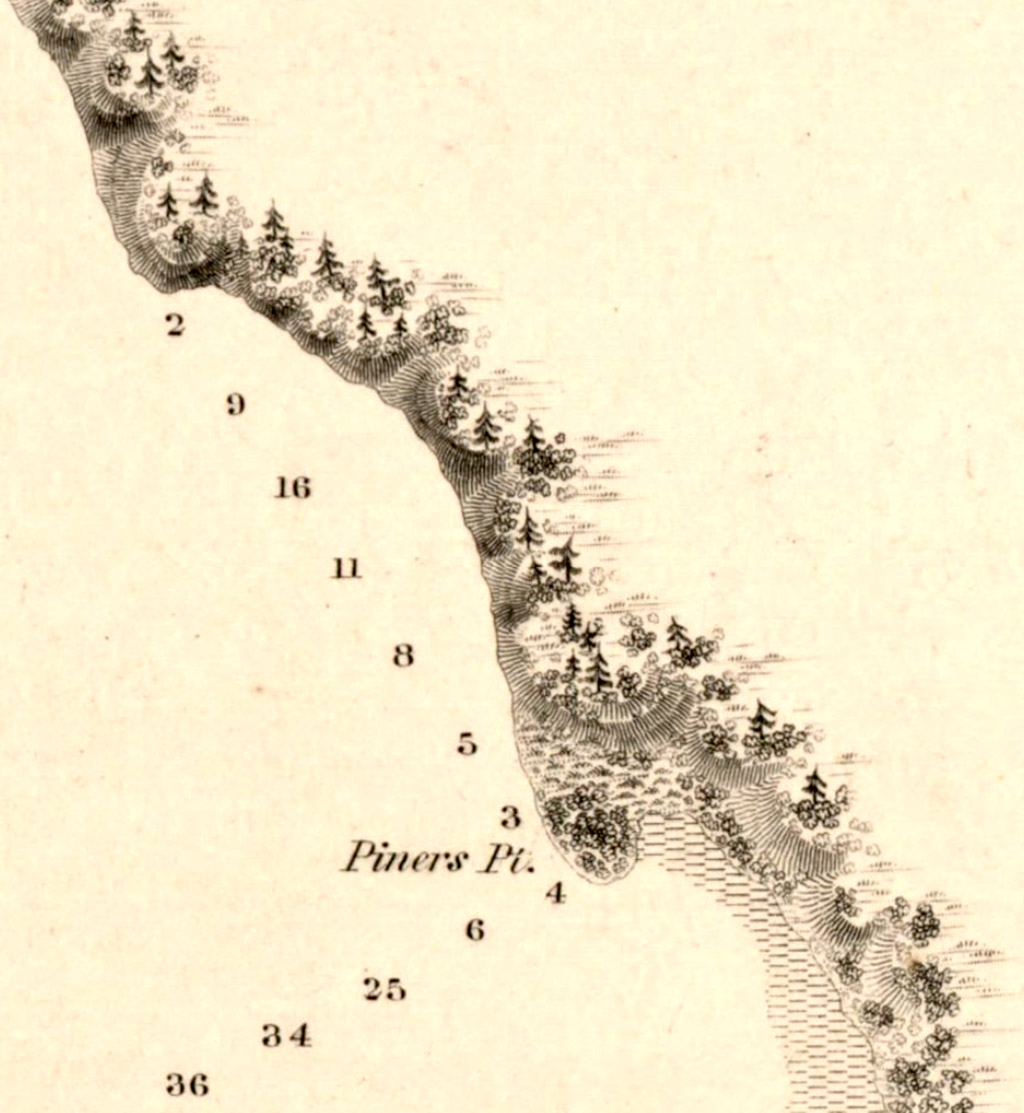

Original shoreline southern point

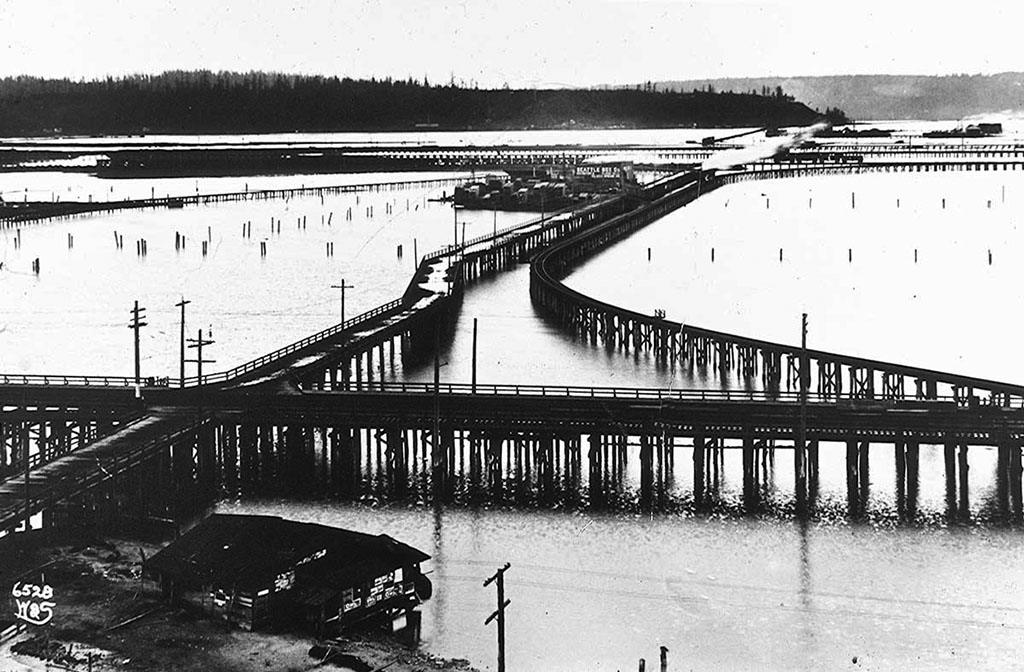

Weller Street Bridge

End of pedestrian bridge extending west of 4th Avenue South at Weller Street

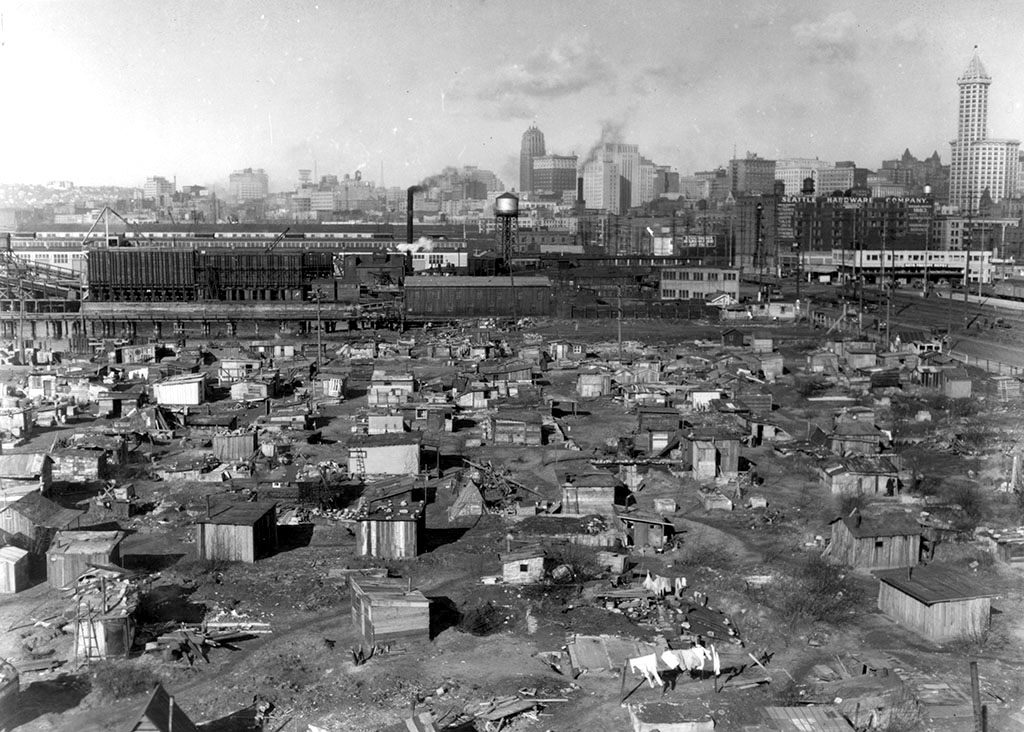

At the end of the pedestrian bridge, just before the steps, turn and look south, toward the football stadium. All the flat lands that you can see — south past Lumen Field to Spokane Street and west to the Port of Seattle’s cranes – were tide flats before seawalls built in the 1910s along East Marginal Way held back the saltwater. The low land was raised with fill from regrades and dredging projects that shaped the adjacent hillsides into workable terrain for city building and carved shipping channels into the mouth of the river. The new land made room for industry and shipping facilities but it decimated the estuary, the mixing zone of fresh water from the river and saltwater from the bay supported a rich array of flora and fauna and provided a transitional space for juvenile salmon making their way to sea from the river’s spawning grounds. Coupled with other fill, drainage, and seawall projects in the area, the loss of the Duwamish River estuary undermined local Indigenous peoples’ ability to fish for a variety of species and gather plants and shellfish that are economically and culturally significant.

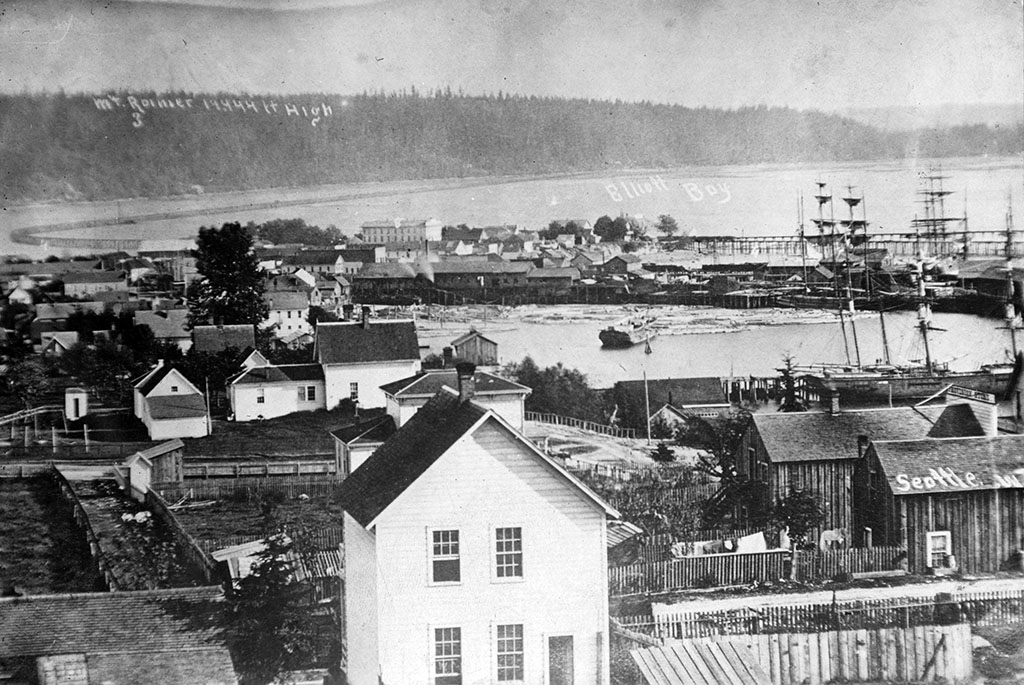

Cross to the other side of the bridge and look toward downtown. The area northwest of King Street Station was a tidal lagoon protected from the bay by a small peninsula of land extending south from about today’s Main Street is to Kind Street along 1st Avenue. It was visited by Coast Salish people, members of today’s Duwamish, Suquamish, Muckleshoot, Snoqualmie, and Tulalip tribes, who fished for flounder and visited a spring on the hillside for fresh water. Coast Salish people know this area and the village located here as Dzidzilalich (Little Crossing-Over Place) likely because of a path that led to the lagoon and another path over the hill to Lake Washington, along the route of today’s Yesler Avenue.

Prior to the filling of the tideflats, the area surrounding the lagoon and extending north to about Yesler Way was the only level land adjacent to the deep-water harbor. Native people’s canoes easily landed at beaches all along the bay, but non-Native sailing ships needed piers that could stretch out to deep water. Once the shoreline north of King Street filled with piers, filling land to the south became appealing so the harbor and the city could continue to grow. The environmental and cultural effects of the loss of wetlands and the plants, shellfish, and fish that lived in them are still felt today.