-

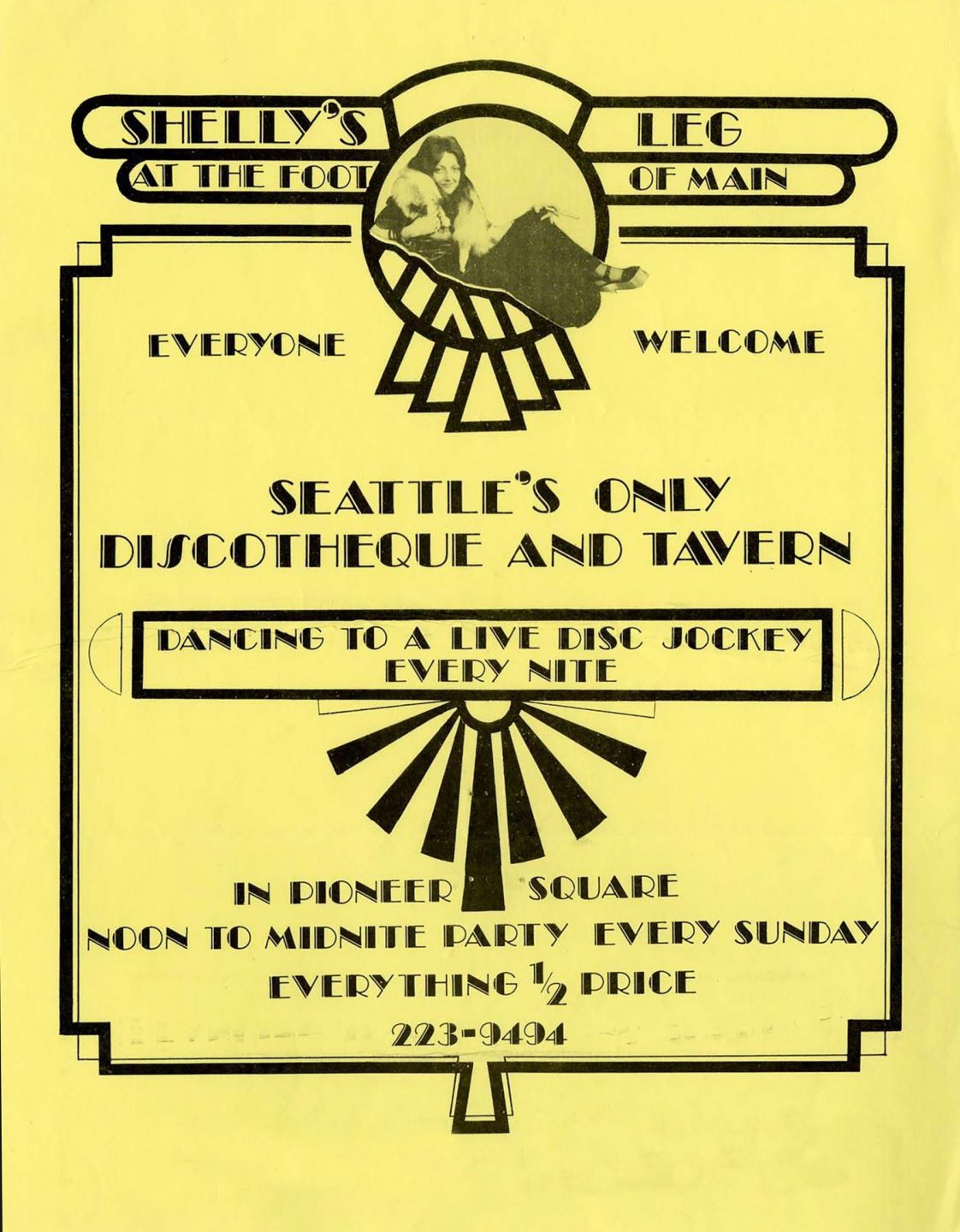

Shelly’s Leg

77 S Main Street

The 4-by-8 sign above the bar said it all: “Shelly’s Leg is a GAY BAR provided for Seattle’s gay community and their guests.” It was a bold proclamation for Seattle’s first disco, a place that was, for a while, one of the city’s most dynamic nightlife venues. And it all grew out of a cannon misfire that nearly took someone’s life.

The cannon was a feature of a 1970 Bastille Day parade, though its presence reportedly hadn’t been requested. Parade organizers instead wanted a fire truck, which a local named Morris Hart, who operated an antique shop in Pioneer Square, supplied. For some reason, Hart opted to include a confetti cannon, and he attached it to the rear of the truck. The cannon possessed a three-foot barrel, and inside its interior tube, called a bore, Hart and his son stuffed two ounces of black powder and shredded paper.

The fire truck pulled the cannon through the streets of Pioneer Square, a spectacle that drew a crowd. Among the spectators was a transplant from Florida named Shelly Bauman. Sometime after 11:30 pm, excited parade-goers climbed atop the cannon where they lit fireworks. Perhaps because of the weight of those gathered on top, the barrel, which had been pointed skyward, descended until it aimed into the crowd. The cannon fired.

For reasons that remain unclear, the confetti paper inside had wadded together. The wad struck Bauman in the abdomen and knocked her onto Occidental Street. Her wounds were grave. Near death, she was transported to a hospital, where surgeons cut into her pelvic bone and amputated her left leg. She underwent subsequent operations, resulting in a nine-month recovery. Bauman, who would require a wheelchair for the rest of her life, sued Hart, parade organizers, and the City of Seattle, whose police officers she alleged ignored a loaded weapon at a public event. In a 1973 out-of-court settlement, Bauman won $330,000.

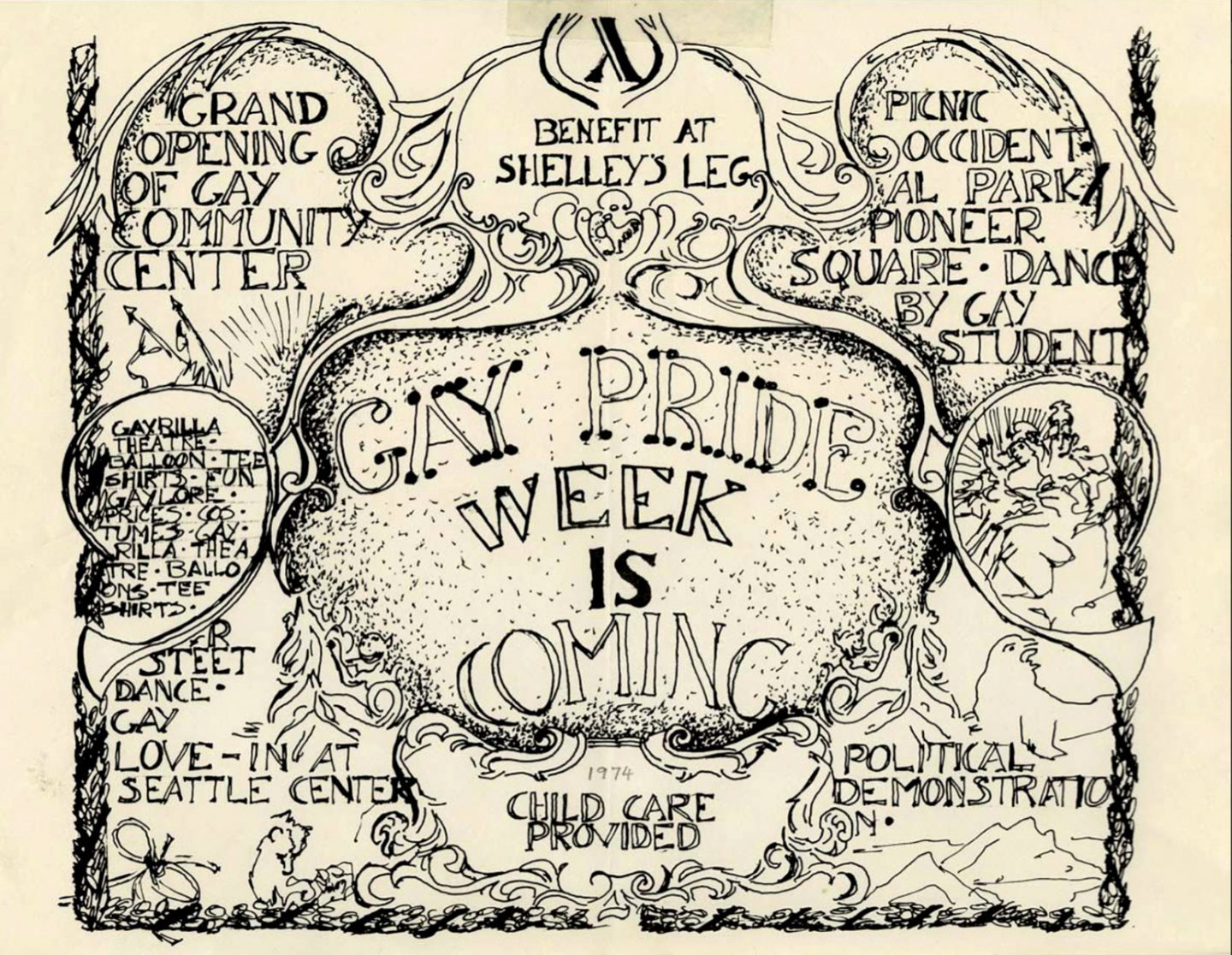

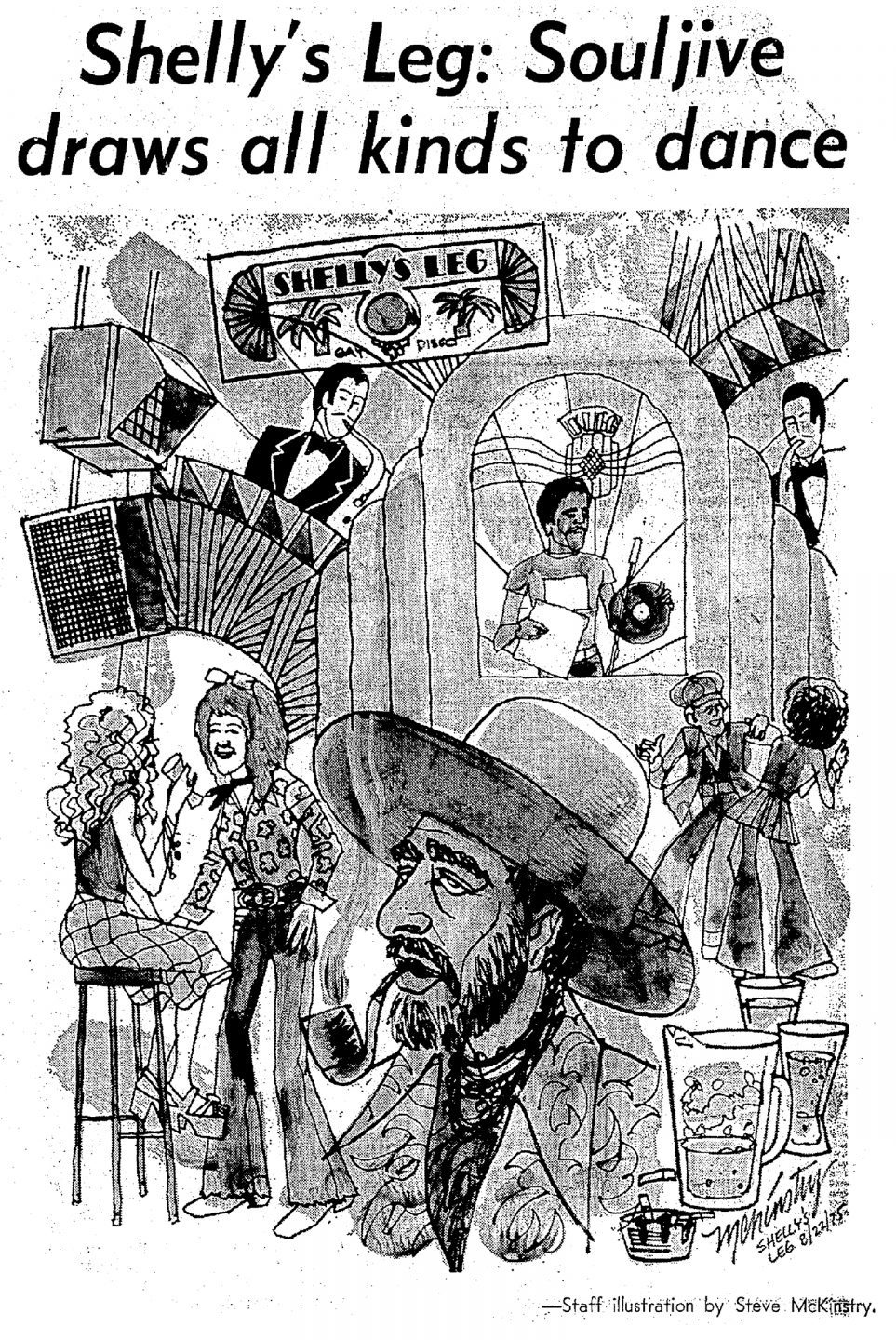

Before the accident, Bauman had befriended several gay men who shared a house. One of them was Pat Nesser, who wanted to open a bar. Another roommate, Joe McGonagle, had experience operating an LGBTQ+ bar in Pioneer Square, but was leery of reentering the business. At some point, his attitude shifted, and Bauman dipped into her settlement to manifest their “fantasy bar.” She lent Nesser and McGonagle about $20,000, and the funds were used to buy the Our Home Hotel. For décor, they chose an art-deco interior with fake palm trees and a chandelier. The space boasted the largest dance floor in Seattle’s LGBTQ+ scene, and it drew throngs of partyers, regardless of sexuality. Famous people joined the masses, including Sylvester, a Black, gender-fluid singer-songwriter whose gospel-infused falsetto powered multiple disco hits, as well as members of one of the world’s most famous rock bands, Led Zeppelin.

Before the disco had opened, owners had proposed several names, many of which state licensers deemed too sexual. Of the names approved, Nesser settled on one that honored his friend: “Shelly’s Leg.” A legend was born. But legends don’t live forever — and a couple of years after it opened, another wad of paper played into the club’s fate.

When Shelly’s Leg was built, the Alaskan Way Viaduct ran along the waterfront, and on December 4, 1975, a tanker truck trundled south along the viaduct. Inside the tanker was 3,700 gallons of gasoline, and an attached trailer carried 4,800 gallons more. The driver lost control, the truck hit a guardrail, and the trailer unhitched. It exploded. Flaming gas rained on a passing train below and cars parked near the Leg. The train cars contained potash and paper products, absorbing the flames. The Leg’s front windows were blown in, and the more than 150 dancers inside escaped through a side door. It turned out to be the start of last call. Even though the Leg reopened, it never recovered. It closed in 1977.

The Leg is now a law office.

Return to 1st Avenue, turn left (north), and proceed to our next stop.